| Date: | December 1844-January 1845? |

| Form: | Eleven ljóðaháttur strophes. |

| Manuscript: | ÍB 13 fol. (facsimile KJH216-18; image), in all essentials the same as the text published in Fjölnir. |

| First published: | 1845 (8F54-7; image). |

| Sound recording: | Dick Ringler reads "Journey's End."  [2:03] [2:03]

Silja Aðalsteinsdóttir reads "Ferðalok."  [2:11] [2:11] |

Hannes Hafstein stated in 1883 that "Journey's End" was written during the final, depressed winter of Jónas's life. It was at that time, says Hannes, that "the memory of forgotten love affairs from his school days revived, surfacing in the exquisite poem 'Journey's End'" (BXXXVIII).

Nothing more concrete about the poem's origins was forthcoming until 1925, when Matthías Þórðarson published his important article "Journey's End" ("Ferðalok"; 9Iðu169-74), in which he showed that the girl whom Jónas recalled so poignantly in this poem was named Þóra Gunnarsdóttir and she and Jónas had fallen in love in July 1828 when Jónas — on his way home to Steinsstaðir for the summer after completing his fifth year of school at Bessastaðir — accompanied the pack train of Þóra's father, Reverend Gunnar Gunnarsson, north from Reykjavík to Eyjafjörður (where Gunnar had been given the pastorate at Laufás).

Matthías says that the source of his information was Þóra's much younger half sister, Kristjana Havsteen (born 1836),3 who had obtained her knowledge partly from her mother Jóhanna Gunnlaugsdóttir Briem (who had obtained it directly from her husband, Þóra's father), and partly from an unidentified female friend of Þóra's.

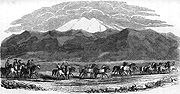

Þóra had been born on 4 February 1812 and was some four years younger than Jónas. In the summer of 1828, when the events in question are supposed to have occurred, she was sixteen, "an extremely lovely and promising girl, adored by everyone" (5DXL). Reverend Gunnar with his pack train and its attendants, accompanied by Þóra and Jónas, took the usual inland route (the old Skagfirðingar Track) from Kalmanstunga in Upper Borgarfjörður, travelling northeast across Eagle Lake Highland (Arnarvatnsheiði) and Big Sands (Stórisandur). It was in these highland surroundings that Jónas's and Þóra's love blossomed; it was here that he "held [her] on horseback / in the hurtling stream" — probably as they rode double across the dangerous Blanda Fords (Blönduvöð).4 A few kilometers farther on he combed her hair — a touching sign of their growing intimacy — on the banks of Boar River (Galtará), a tiny tributary of the Blanda, where the party may have paused to rest its horses or camp for the night (cf. 12Iðu278).

"Journey's end," for Jónas, came when they reached his mother's farm at Steinsstaðir after a trip from Reykjavík that had probably taken 3-4 days. Here the lovers parted. Before they did so, however, Jónas asked Þóra's father for her hand in marriage. Reverend Gunnar told him that the pair were too young to be formally engaged: "The future was uncertain, he said, and it would be best to see how their situations developed during the next few years and whether they remained attached to each other" (5DXLI). Perfectly sensible. After all, Þóra was only sixteen, and Jónas was still a student at Bessastaðir.

We are told that the pair exchanged letters for a while but in all likelihood never met again. Jónas did not go out of his way to look Þóra up and two or three years later he seems to have had another woman in mind as a prospective bride (see ÁBT54-9). In 1832, not long after Jónas sailed for Copenhagen, Þóra was betrothed by her father to a clergyman fourteen years older than herself whom she married ("half-unwilling" it is said) in 1834. Some dozen years later, not long after Jónas's death, she is reported to have heard "Journey's End" read aloud at a wedding feast, to have realized how deeply he had loved her (and that he had never forgotten her), and to have been so overcome with sorrow that she took to her bed. She outlived Jónas many years, dying of typhus in 1882.

In 1832, not long after Jónas sailed for Copenhagen, Þóra was betrothed by her father to a clergyman fourteen years older than herself whom she married ("half-unwilling" it is said) in 1834. Some dozen years later, not long after Jónas's death, she is reported to have heard "Journey's End" read aloud at a wedding feast, to have realized how deeply he had loved her (and that he had never forgotten her), and to have been so overcome with sorrow that she took to her bed. She outlived Jónas many years, dying of typhus in 1882.

All this is the stuff of which legends are made, of course, and "the bittersweet love of Jónas and Þóra has become one of Icelanders' best known love stories" (ÁBT80).

It is not known with certainty when "Journey's End" was written. As noted earlier, Hannes Hafstein — probably on good authority — believed it to be a product of Jónas's last winter. The surviving manuscript points in the same direction, since it dates (probably) from early January 1845 (see KJH314). There is plainly a close connection between "Journey's End" and Jónas's poem "Quatrains" ("Stökur"), and since "Quatrains" can be dated precisely (21 December 1844), it is likely that "Journey's End" was written around the turn of the year 1844-5. Matthías Þórðarson's argument that it was composed at Steinsstaðir in 1828, immediately after Jónas and Þóra had parted, can no longer be given much weight (see Kf161-86). Matthías took the combination of present-tense verbs with precise topographical allusions, in strophes 1-3 and 10, to imply that these parts of the poem must actually have been composed in the surroundings they describe, whereas a glance at Jónas's late cycle of topographical poems, with their intricate interweaving of topography with past and present time, ought to have pointed him in a different direction. Indeed, much of the controversy about the dating of "Journey's End" has occurred because of Jónas's deliberate blurring of the boundary between past and present. In the surviving manuscript we actually catch a glimpse of him engaged in this chronological prestidigitation. The second half of strophe 9 originally read (before he altered it):

eye stars flashed,

flower lips smiled,

cheeks turned ruby red —

which is obviously much more true to the real "time-facts." (Similarly, in the fourth line of strophe 8, Jónas first wrote "could," then altered this in the manuscript to "can," then reverted in the published version to "could"!) The deliberate confounding of past and present, throughout the poem, serves to suggest that love triumphs over time, just as it triumphs over space (as is asserted in the final strophe).

After taking leave of Þóra in 1828, Jónas went on to have relationships with several other women, so the poignant, reawakened memories in "Journey's End" are more likely to be a symptom of his generally depressed mood, in the last winter of his life, than of any obdurate lifelong obsession.

In light of the oral traditions about the poem's origins, which seem as authentic and well-authenticated as such things can be, it would be perverse to deny the presence of a strong autobiographical element in "Journey's End." On the other hand, in a poem that was probably written about the same time as the topographical poems mentioned above and that deals (like them) with memories of travel in Iceland, it is not at all likely that what we have is an attempt at reportage or reconstruction of actual facts, but rather extremely probable that there is an imaginative (and even imaginary) dimension to the experiences recounted in the poem.

Revisions in the surviving manuscript show that at first Jónas gave it the title "My Love" ("Ástin mín"). This phrase is ambiguous and can be taken as answering either the question "Who is she?" or the question "What is its nature?" — or indeed both questions at once (see Kf172). Jónas subsequently altered the title to "An Old Story" ("Gömul saga"), which may have had ironic overtones.5 Finally he settled on "Journey's End" ("Ferðalok"), the magnificently suggestive title under which the poem was published in the eighth issue of Fjölnir several weeks before the accident that caused his death.6

"Magnificently suggestive" because this title, in addition to referring to Jónas's parting from Þóra in the summer of 1828, can be read as alluding to his attainment, as the fruit of his life's journey, of the knowledge expressed in the poem's last strophe (knowledge of love's eternality) — and beyond this, more darkly, as referring to death itself, that ultimate and universal "journey's end." Death was something very much on the mind, in his last days, of this much-journeyed man.

Steeple Rock (Hraundrangi), which plays so central a role in the poem, is a prominent spire of basalt that towers above the farm Hraun (where Jónas was born) and dominates the southwestern horizon from Steinsstaðir (where he spent his boyhood).7 The "star of love" is the planet Venus, imagined as an evening star in the sky above Steeple Rock and symbolizing Þóra and/or Jónas's love for her. The speaker's reference in strophe 2 to a world flaming with the fire of God may well continue the astronomical allusion, conjuring up the image of a planet (or better, half a planet) illuminated by the sun around which it revolves. The poem ends with another astronomical allusion, and its climactic last strophe owes much of its power to Jónas's intense awareness of celestial distances — an awareness fostered by his scientific studies at Copenhagen and deepened by translating Schiller's "The Vastness of the Universe" and G. F. Ursin's handbook on astronomy.8

The "mystical" statements (about the relationship of love, God, time, space, and eternity) that impart such force to strophes 2-3 and 11 of the poem find their theoretical basis — if not their actual source — in a passage from J. P. Mynster's Meditations on the Principal Points of Christian Faith, a work translated by Jónas and his two closest Fjölnir colleagues and published in 1839:

I can truthfully say that my love is not bounded by time or space. It accompanies those I love when they are far away and even brings me — from their graves — those who have long been dead, for individuals who love each other with their whole heart are always near each other [

því þeir sem unnast hugástum, þeir eru ætíð hver öðrum nálægir]. And yet, all this is nothing but a dim shadow of the nearness of the infinite God throughout all of measureless space and everlasting time (

Hhk47).

9

The idea expressed in strophe 7 (i.e., that elves anticipate the tragedies lying in wait for human beings by shedding tears of prophetic sympathy) may well derive from two lines at the beginning of the eddic "Lay of Hamðir" ("Hamðismál") which mention "cheerless events that make the elves weep" (literally "the joy-deprived tear-causations of elves," græti álfa / in glýstavmo [Rask]). Since the elves of Icelandic folklore were generally believed (at least in Jónas's day) to be human-size beings who inhabit hills and rocks and cliffs, the "flower-elves" of "Journey's End" are likely to be at least partly non-Icelandic in literary lineage. In H. C. Andersen's "The Travelling Companion" ("Reisekammeraten" [1835]), for example, we find tiny elves — some no bigger than a man's finger — who spend the night laughing and playing with dewdrops among the leaves and tall grass, then climb back into their flowers at dawn (see 1HCA71).

Strophes 4-7 of Jónas's poem, describing the awakening of the young couple's love, seem to take place at dawn ("while heaven grew clear, / bright at the mountain brim"); strophes 8-9, describing their growing intimacy, in broad daylight; strophes 1-3 and 10 (which frame the narrative) at night. This can hardly be accidental and gives the poem both temporal structure and great suggestive power.

One of the most interesting features of "Journey's End" is the way in which it succeeds in snatching victory, of a sort, from the jaws of defeat and despair. Originally, in the surviving manuscript of the poem, the last three lines of strophe 10 were identical with the first three lines of strophe 1, consequently the transition from the flat pessimism of strophe 10 to the exalted conviction of strophe 11 was abrupt and unmediated. Jónas later altered these lines (in the manuscript) to the form they have in the published text, thus neatly bridging the gap. The "star of love" may be "back of clouds" — but it is still burning.

There is a strong current of pantheism running in this poem,10 and it is fascinating to observe its dynamics. Þóra is a flower, her lips are flowers, her eyes are stars. Now, it is one thing to use metaphors like these — as they were regularly used by both Oehlenschläger and Heine, for example — in contexts where they reflect nothing more than an easy and hackneyed tradition. It is another thing altogether to use them in a poem full of real heavenly bodies and real flowers and grasses. The effect of these juxtapositions is to suggest that flowers and stars and human beings are all

like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree;

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first, and last, and midst, and without end,

as Jónas's English contemporary William Wordsworth put it in The Prelude (VI:636-40). Jónas's inchoate pantheism, implicit throughout the poem in its image-system, also helps account for the semi-mystical statements in strophes 2 and 3. Jónas's leaning toward pantheism, evident in a number of works (see, for example, the "Lay of Hulda"), may have been sharpened by his recent reading of Ludwig Feuerbach.

Hannes Pétursson has interpreted the last strophe of Jónas's poem as a deliberate rejoinder to the concluding stanza of Bjarni Thorarensen's well-known "Lay of Sigrún" ("Sigrúnarljóð"), where the bodies of two dead lovers ascend to the skies, there to embrace and disport themselves. According to Hannes, Jónas rejects this notion. As Jónas sees it, a man's

dead body descends to the grave and there it turns to dust.

"Earth will clasp his corpse to her" — those are the only embraces he will ever enjoy. But the

spirit of the lovers lives on, without any of their earthly garments: "souls that are sealed in love" are eternally united, in spite of the separation that reigns everywhere in the phenomenal world. (

Kf184)

But did Jónas really believe, after reading and pondering Feuerbach, that lovers' spirits (or souls) will live forever after their death? True, he asserts that "not even eter- / nity can part / souls that are sealed in love." But what does he mean by "eternity"? Is it not, perhaps, simply the "eternity" of Feuerbach?

According to the distinguished Icelandic poet Davíð Stefánsson (1895-1964), "Journey's End" is "the nation's most beautiful poem" ("landsins fegursta kvæði").  Davið offers this opinion in a fine poem of his own entitled "Remembrance" ("Minning"), which is imagined as being spoken by Þóra Gunnarsdóttir near the end of her long life. "Journey's End" and its associations have always been very dear to Icelanders, and it is largely because of the celebrity conferred upon Steeple Rock by Jónas's poem that the architect Guðjón Samúelsson (1887-1950) designed the two towers of Hallgrímskirkja (Hallgrímur's Church) in Reykjavík to imitate it and its attendant spire.11

Davið offers this opinion in a fine poem of his own entitled "Remembrance" ("Minning"), which is imagined as being spoken by Þóra Gunnarsdóttir near the end of her long life. "Journey's End" and its associations have always been very dear to Icelanders, and it is largely because of the celebrity conferred upon Steeple Rock by Jónas's poem that the architect Guðjón Samúelsson (1887-1950) designed the two towers of Hallgrímskirkja (Hallgrímur's Church) in Reykjavík to imitate it and its attendant spire.11

Bibliography: Hannes Pétursson's chapter "Aldur Ferðaloka" ("The Date of 'Journey's End'") in his book Kvæðafylgsni (Kf) is essential for the study of the poem. See also Dagný Kristjánsdóttir, "Ástin og guð: Um nokkur ljóð Jónasar Hallgrímssonar" (50TMm341-60, esp. pp. 349-53); she argues that "Journey's End" is "about love, about yearning for the most intimate relationship it is possible to form with another human being, doubt that it can really be achieved, fear that it is all mere deception, and conviction that reality is of less importance than that deception: the dream about love" (353). See finally Guðmundur Andri Thorsson, "Ferðalok Jónasar" (51TMm45-53), which sees connections between this poem and "Gathering Highland Moss" and suggests that "Journey's End," too, is about sibling love.

Notes

1 See "Hávamál", strophe 98. [Jónas's note. In the strophe indicated (which is numbered 97 in present-day editions) the god Óðinn finds himself attracted to a certain "sunwhite maiden" and says: "Delight did not seem to me to exist at all apart from living with that body." The strophe-number cited by Jónas seems to derive from Rask's 1818 edition of the Poetic Edda, the reading in line 4 (alls yndi) from Resen's 1665 edition (see Sveinn Yngvi Egilsson, "Eddur og íslensk rómantík: Nokkur orð um óðfræði Jónasar Hallgrímssonar," Snorrastefna 25.-27. júlí 1990, Ritstjóri Úlfar Bragason [Reykjavík: Stofnun Sigurðar Nordals, 1992], p. 259, n. 11).]

2 Sb. Hávamál 98. er. [Athugasemd Jónasar.]

3 Kristjana was Hannes Hafstein's mother. It is a pity that Hannes — who must have been thoroughly knowledgeable about the whole business — should have been so reticent in his biographical sketch of Jónas (see ÁBT64-5).

4 Presumably Þóra sat in front of Jónas on horseback, riding sidesaddle and facing to the left, while he held her with his left arm and guided the reins of the horse with his right hand. Riding double across the Blanda was dangerous. In 1829, the year after the journey described in Jónas's poem, a boy and girl drowned while trying to do so (1Ana409).

Many years later Jónas described the crossing on the River Blanda as follows:

Up on Eyvindarstaðir Heath the river flows in multiple channels over level tracts of sand. It can be crossed at the so-called Blanda Fords, which are extremely convenient but need to be approached with a good deal of caution, since the stream is constantly recutting its channels. These Fords are located on the Skagfirðingar Track and everyone whose route lies across Big Sands from Borgarfjörður to Skagafjörður crosses the Blanda at this point. (

3E156; the first two sentences are taken almost word for word from

HSs107.)

5 The last stanza of a bitterly ironic love poem of Heine's (Lyrisches Intermezzo XXXIX) may have been on Jónas's mind when he coined this alternate title:

Es ist eine alte Geschichte,

Doch bleibt sie immer neu;

Und wem sie just passieret,

Dem bricht das Herz entzwei. (1HHS79)

6 The issue was in print by 6 May 1845 (see BPB77); Jónas's accident occurred the night of 20/21 May.

7 Hraundrangi was associated in Icelandic folk tradition with the outlaw-hero Grettir the Strong and was even known locally in Öxnadalur as "Grettisnúpa" ("Grettir's Crag"; 2Íþs571). Grettir was said to have climbed to its top and left his knife and belt there as proof of the fact, saying that anyone who was able to retrieve them could keep them. ("So far, however, no one has taken him up on this, since no one believes it possible to make the climb" [2Íþs99].) Konrad Maurer was told this story at Steinsstaðir in 1858 by Stefán Jónsson, the second husband of Jónas's older sister Rannveig (IVG222-3; KMÍ154); Jónas himself must have known it from boyhood. It may have influenced his surprising (and brilliant) choice of a knife as one of two climactic symbols in the final strophe of "Journey's End": visualizing the evening star in the sky above Hraundrangi, he also visualizes — perhaps half unconsciously — the knife that hangs at its summit, one as unattainable as the other.

8 See 3E314-7 for Ursin's (and Jónas's) striking imaginative representation of the immense distances between the worlds (knettir) in "heaven's abyss" (himingeimur); see also 3E413-5.

9 The suggestion in the poem that something that has happened once has happened forever may be indebted in part to Jónas's reading of Feuerbach:

Im Einmal endet Zahl und Zeit,

Drum ist das Einmal Ewigkeit. (

1FFS368)

10 Pantheism is the belief that God and the universe are identical and God is therefore present in all things. A good example of pantheism in Jónas's earlier writings is the cancelled passage of "The Lay of Hulda" in which he describes Eggert Ólafsson's wish "that the world should perceive God and itself in every blade of grass". The pantheistic tendency in Jónas was first recognized — or at least labelled — by Halldór Laxness in his famous essay "Concerning Jónas Hallgrímsson" ("Um Jónas Hallgrímsson" [1929]). Laxness employs the word algyði ("pantheism") and speaks of Jónas's "invocations to a pantheistic God" (ákallanir á panþeiskan guð) (Ab56).

11 See Íslenzk bygging: Brautryðjandastarf Guðjóns Samúelssonar, Texti og ritstjórn: Jónas Jónsson og Benedikt Gröndal ([Reykjavík]: Bókaútgáfa Norðri, [1957]), p. 13.