| Date: | March/April 1844. |

| Form: | An "Italian" sonnet rhyming ABBA ACCA dEf dEf (the translation rhymes ABBA CDDC eFg eFg) and with the alliteration pattern 22 22 21 21. |

| Manuscript: | KG 31 b IV, where it has the title "Ég bið að heilsa" (facsimile KJH183; image). |

| First published: | 1844 (7F105-6; image) under the title "Ég bið að heilsa!" |

Jónas seems to have regarded the poem as a sort of generic greeting to his native land and all his friends and acquaintances there. At least he wrote Páll Melsteð on 5 July: "I took some precautions, this past spring, and sent my greetings home with good old Fjölnir, since I knew I wouldn't be writing a lot of letters to people — any more than usual" (2E213-4).

It seems likely that "I Send Greetings!," and especially its last three lines, recycle material from a poem written in 1832 when Jónas was en route from Iceland to Copenhagen for the first time. In this poem, composed when the ship and its passengers were sailing eastward in the teeth of adverse weather, Jónas asks the wind why it is so bent on holding up their progress toward Norway and Denmark. The wind explains that it feels like blowing westward toward Iceland:

"I am filled with longing

to enfold her hills,

crown them with golden clouds,

and down in deep

dales to kiss

girls with gorgeous hands."

That's very nice, says the poet. But please go about, now, and blow from the other direction:

"Blow from the west,

oh wind! laden

with airs from Iceland's valleys!

Waft me the kisses —

cordial and sweet —

of the dales' lovely daughters!"1

In the surviving manuscript of "I Send Greetings!" the girl alluded to in the last three lines of the poem has "a green tassel" on her cap. In the version printed in Fjölnir, however, not only has the tassel become red but this adjective is given striking emphasis by being printed with wide internal spacing (the equivalent of italics).

Dick Ringler and Áslaug Sverrisdóttir have argued that in Jónas's day the silk tassels on the caps (skotthúfur) of Icelandic women were predominantly green in color and that the manuscript version of Jónas's poem thus reflects contemporary usage and is intended to evoke familiar and comfortable emotions. They go on to argue that the red tassel of the Fjölnir version of Jónas's poem represents a startling innovation: it is an Icelandicization of the bonnet rouge of the French Revolution, and Jónas's "Greeting" is thus intended as a challenge to his countrymen to persevere in — and even intensify — their struggle for increased independence from Denmark. In the early nineteenth century the "radical redness" of the bonnet rouge was recognized everywhere in Europe and the Americas and, thanks to the July Revolution of 1830, had recently figured prominently in the "Schlußwort" of Heinrich Heine's Reisebilder (the relevant section of which had been translated by Jónas and Konráð Gíslason and published in the first issue of Fjölnir [1F141-4]). It had also recently been immortalized in art by Eugène Delacroix in his painting "La Liberté guidant le people" (1831), which Jónas is likely to have known — if not by hearsay or through reproductions — then at least through the elaborate description by Heine in his Franzöische Maler.

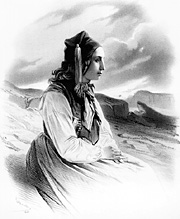

Thus, while remaining at one level an ordinary Icelandic girl, at another level the woman to whom Jónas sends greetings in his poem is likely to be — like Delacroix's female — an allegorical figure who represents the nation and its liberty or freedom. She may even merge together, in Jónas's conception, with the allegorical figure of Iceland as Fjallkonan ("The Lady of the Mountains"):

The national symbol that emerged during the independence movement,

Fjallkonan (the Woman of the Mountain), encompassed both Icelandic nature and Icelandic culture. . . . While she symbolized what Icelanders considered to be genuine and purely Icelandic, in her purity she reflected a deep-seated, but unattainable, wish of Icelanders to be a totally independent nation.

Fjallkonan is thus not only a national symbol, she also represents the national vision, the nation's ultimate dream.

2

There are two prior English translations of Jónas's poem, one ("A Greeting") by Jakobina Johnsen (IL57, 59), the other ("Greeting") by Watson Kirkconnell (NAB133-4).

Bibliography: See Dick Ringler and Áslaug Sverrisdóttir, "Með rauðan skúf," 172Skí279-306. There is an appreciation of Jónas's poem, interesting if somewhat subjective, by Kristinn E. Andrésson: "Ég bið að heilsa," Rauðir pennar (Reykjavík: Bókaútgáfan Heimskringla, 1935), pp. 257-65 (reprinted in Eyjan hvíta: Ritgerðasafn [1951], pp. 9-16, and again in Ritgerðir, I [Reykjavík: Mál og menning (1976)], 75-84).

Notes

1 These are the fourth and sixth strophes of a six-strophe poem in ljóðaháttur, composed at sea on 31 August 1832. The poem, untitled in the manuscript (KG 31 b III [facsimile KJH60-2]), was first printed in 1847 (A47-9) under the title "Í spánska sjónum" ("In the Spanish Sea"), this being, apparently, a designation for the ocean to the north and northwest of Scotland.

2 Inga Dóra Björnsdóttir, "Public View and Private Voices," in The Anthropology of Iceland, ed. E. Paul Durrenberger and Gísli Pálsson (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989), p. 107. The symbol of Fjallkonan seems to have originated with Eggert Ólafsson in 1752, to have been further developed by Bjarni Thorarensen in "Íslands minni" (written ca. 1805-8), and to have been adopted subsequently by a number of poets, including Sigurður Breiðfjörð in "Fjöllin á Fróni" (1833) and Jónas in his "lay of Magnús" (1842), where she is mentioned no fewer than four times. (See JH19-22 and Gamlar þjóðlífsmyndir, Árni Björnsson skrifaði texta, Halldór J. Jónsson sá um myndaval [Reykjavík: Bókaútgáfan Bjallan, 1984], p. 151.)