| Date: | Summer 1837. |

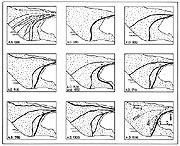

| Form: | 82 five-stress lines. The rhyme scheme (of the original) is: AbA bCb CDC DeD eFe FGF GHG HiH iJi JkJ kLk LmL mNm NoN oPo PqP qRq RsR sTs TUT UVU VwV wPwPwPXX eYeYeYZZ. The alliteration pattern (of both original and translation) is: 21 12 21 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 111 21 21 22112 2222. |

| Manuscript: | None surviving. |

| First published: | 1838 [actually 1839] (4FI/31-4; image) under the title "Gunnarshólmi." |

| Sound recording: | Þorleifur Hauksson reads "Gunnarshólmi."  [5:06] [5:06] |

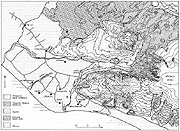

The area of which this river has already taken possession in its comings and goings, and in the various alterations of its bed, is certainly more than two leagues across, although in and of itself — and in ordinary circumstances — it is a stream that would hardly deserve any notice at all. (

5VIG214)

In 1934-46 a system of artificial embankments was built to control Wood River's flow and protect the cultivated areas of the outwash plain from erosion.2

In ordinary usage a holm (hólmi or hólmur) is an islet in a river. In Jónas's poem the word is used of an uneroded "island" of grass in the waste of sand and gravel created by Wood River's migrations and inundations.

This holm is named "Gunnar's Holm" after Gunnar Hámundarson from Hlíðarendi, one of the main protagonists of Njál's saga.

Gunnar is the most attractive and unreservedly admired of Icelandic saga heroes. Tricked by his enemies into disobeying the warnings of his prescient friend Njáll and killing twice in the same family, he is sentenced at the Alþing to three years' exile in Norway. Njáll tells Gunnar that if he accepts this sentence and goes to Norway, he will return to Iceland more famous than ever and will live to be an old man; if he remains in Iceland, however, he will die. Gunnar arranges passage on a ship and early one morning, bidding farewell to family and friends at home, he and his faithful brother Kolskeggur (who has received an identical sentence) set off on their journey.

They rode down to Wood River. There Gunnar's horse stumbled and he leaped from the saddle. Glancing up toward the slope and his farm at Hlíðarendi he said: "How beautiful the slope is! It has never seemed so beautiful before, with its ripening grain and new-mown hay. I am going to ride back home and not go abroad."

"Don't do your enemies such a great favor," said Kolskeggur, "breaking your agreement. Nobody dreams you would ever do a thing like that. And don't forget: it will all turn out as Njáll says."

"I am not going to leave," said Gunnar. "And I wish you would stay too."

"Not for worlds," said Kolskeggur. . . . There the brothers parted. Gunnar rode back to Hlíðarendi and Kolskeggur carried on to the ship and sailed abroad (2Ífr182-3)

Gunnar's sudden decision to change his plans leads to his death the following year.

The success of Jónas's poem is largely dependent on the way in which its message of patriotism and loyalty to Iceland is embodied in a concrete yet symbolic example. The river of time and change, endlessly flowing, has washed away the glories of Iceland's heroic past, but Gunnar's Holm has survived into the present as the objective correlative of the memory of Gunnar himself: a man of heroism, energy, virtue, and — above all — unswerving loyalty to the land of his birth and love for its overpowering physical beauty. In "Gunnar's Holm" Jónas has provided a good example of what he had called for, earlier the year he wrote the poem, in his famous essay attacking Sigurður Breiðfjörð and the Icelandic rímur tradition.3 There he says that a narrative poem is only worth reading "if it portrays some remarkable episode in human life, either actual or imaginable, and if it shows the reader the souls of the characters it brings onstage, and if it brings onstage only souls there is some point getting to know" (3FI/20).

Jónas visited Fljótshlíð for three weeks in late June/early July 1837, staying with his friend Tómas Sæmundsson and making the latter's parsonage at Breiðabólsstaður his base-camp for geological sorties in Rangárvalla- and Árnessýslur. During his stay he had plenty of opportunity to familiarize himself with the landscape described in the poem, no doubt even visiting the site identified in local tradition as Gunnar's Holm (BTS214-5). This first-hand experience of the locale was obviously of crucial importance for the creation of the poem.

In Reykjavík, later that same summer, Jónas re-read Njáls saga in order to prepare himself for his visit to Þingvellir in August (2E18). Later still, at the end of the summer, he spent three weeks with his family at Steinsstaðir in Öxnadalur before sailing for Copenhagen (on 24 September). According to his nephew Hallgrímur Tómasson, who was a boy of 15 at the time, the poem was composed during Jónas's last three weeks in Iceland, its immediate inspiration being a visit to Bjarni Thorarensen, the Deputy Governor of the north and east. At least this is what Hallgrímur told Matthías Jochumsson fifty years later and Matthías reported in his journal Norðurljósið:

One lovely summer day in haymaking season, Jónas rode down to Möðruvellir to visit Bjarni, and Hallgrímur rode along with him. When they arrived, Bjarni greeted Jónas warmly and led him to the living room; Hallgrímur was put in a nearby room where he was able to hear clearly what they were saying. He distinctly remembers Bjarni talking about the sagas, especially Njál's saga, and saying it was a pity poets like Jónas and himself didn't more often go to them for subjects. Hallgrímur particularly recalls Gunnar's Holm being mentioned, and it seemed to him that Bjarni was urging Jónas to write about it.

Bjarni, Iceland's most distinguished living poet, would naturally have found the subject a promising one: he himself had grown up at Hlíðarendi, had written a number of poems about Fljótshlíð, and was intimately acquainted with the geography of the area.

After a lengthy visit the two kinsmen took their leave of Bjarni, riding down to Akureyri that evening. The moon was shining and the weather exceptionally mild. On the way Hallgrímur spoke to his uncle, who had been riding along for some time in silence. Jónas replied: "Speak as little as possible right now, nephew. I'm composing a poem."

That night the two of them shared an upstairs room. Hallgrímur went to bed and fell asleep at once; he was not aware that his uncle ever got undressed or went to bed. Instead he sat there at a table composing or writing something. The next day he continued working on it, and late in the day told Hallgrímur to go back home, leaving him behind in Akureyri. He gave Hallgrímur a sealed letter and asked him to put it into the hands of the Deputy Governor on his way back up the valley. With that they parted.

When Hallgrímur reached Möðruvellir and the Deputy Governor inquired about Jónas, Hallgrímur conveyed the latter's greetings and handed over the letter. He learned, then, that what it contained was the poem "Gunnar's Holm."

Bjarni apparently read the poem out loud to those who were present, and his delight was obvious. Matthías Jochumsson continues:

More than fifty years later, Hallgrímur still remembers hearing various expressions of praise and astonishment, among them several that were similar to the words reported to me by the late Rev. Páll Jónsson from Viðvík (who was Deputy Governor Bjarni's secretary at the time). "Now it will be best for me" — or, "Now it's time for me" — "to stop writing poetry," is what they both claim Bjarni said.4

Recent criticism, while not dismissing Hallgrímur's account entirely, tends to be somewhat skeptical about the accuracy of its details, citing the unreliability of Hallgrímur's memory (well attested elsewhere) and the folktale-like character of the story, and also noting "how unbelievable it is that Jónas should have composed such an outstanding poem in only two days" (4E131; see also Kf52).5 As these critics see it, the composition of the poem is much more likely to have occupied Jónas a good part of the summer, beginning perhaps during his three-week stay in Fljótshlíð.

If Hallgrímur's account contains a core of truth, which on the whole seems likely, then it suggests two things about the origin of "Gunnar's Holm." (1) When he wrote the poem, Jónas was nearing the end of his first brief visit to Iceland after an absence of nearly five uninterrupted years in Denmark, and was about to return to his foreign "exile." His own situation was thus very like Gunnar's at the critical moment when the latter decides to remain in Iceland, whatever it may cost him. It is hard to believe that the similarity in their situations did not cross Jónas's mind. (2) The poem was written in part to please (and impress) a distinguished fellow poet and this may go some way toward explaining the extreme elaborateness of its technique.

In the note to readers that Jónas prefaced to "Gunnar's Holm" when it was published in Fjölnir in 1838, he described it with deliberate false modesty as a "little poem" (smákvæði). In fact it is an extremely "big" poem in every respect but line-count (and even in line-count it is among Jónas's longer poems). Its poetic technique is extraordinarily elaborate and sophisticated. From the point of view of form, the poem falls into two sections: sixty-six lines of terza rima (the progressive interlocking form invented by Dante for use in the Divine Comedy), followed by sixteen lines (two stanzas) of ottava rima (another Italian form, first popularized by Boccaccio in the 14th century). Both terza rima and ottava rima were introduced into Iceland by Jónas in this poem. The terza and ottava rima sections are provided with a rhyme-link in lines 65 and 67.6 The sixty-six lines of terza rima are themselves divided into two contrasting passages of thirty-three lines each, the first descriptive, the second narrative. The concluding stanzas of ottava rima round the poem off by suggesting the meaning of its narrative, its symbolic significance, and its relevance to Jónas's own time.

In the terza rima section, both masculine and feminine rhymes appear but do not alternate according to any fixed pattern (the translation reproduces this feature of the original). In this, as in certain other important respects, Jónas's immediate literary inspiration and model seems to have been a poem entitled "Deutsche Barden: Eine Fiktion" by the German poet Adelbert von Chamisso (1781-1838), whose reputation stood at its height in 1837.7 The opening of Jónas's poem bears an astonishing resemblance to the opening of Chamisso's (except for the fact that the scenery in one is Icelandic, in the other German, and the fact that Jónas's poem takes place toward sunset, Chamisso's at dawn)

Es schimmerten in rötlich heller Pracht

Die schnee'gen Gipfel über mir; es lagen

Die Täler tief und fern in dunkler Nacht.

Der frühe Nebel ward empor getragen;

Ich sah ihn in den Schluchten bald zerfließen,

Bald über mich die feuchte Hülle schlagen,

Den Bergstrom hört ich brausend sich ergießen,

Das starre Meer des Gletschers sich zerspalten,

Und donnernde Lauvinen niederschießen.

Ich hatte Müh, den steilen Pfad zu halten,

Auf dem ich klomm zum hohen Bergestor,

Von wo die Blicke ostwärts sich entfalten.

8 (

1CSW381-3)

The central portion of Chamisso's poem is concerned with the Greek struggle for independence ("der Griechen Heldenkampf"). Chamisso speaks of "Die Freiheitssonne Hellas'" and (more generally) of "goldne Freiheit" and suggests that the role of German poets is to sing "Um Freiheit, Recht und Glauben." Jónas and his Fjölnir colleagues would naturally have found such sentiments very attractive.

Jónas might, of course, have become familiar with Chamisso's "Deutsche Barden" earlier than his summer visit to Iceland in 1837. But it is tempting to fantasize that he first encountered it at Möðruvellir in September. Bjarni Thorarensen was well-versed in German literature, and it is pleasant to imagine him and Jónas looking over Chamisso's poem together when discussing how heroic subjects from saga-age Iceland might be handled by poets like themselves.

It has been noted that in the sixty-six lines of terza rima in "Gunnar's Holm," which employ a total of 22 different rhymes, Jónas does not use the same rhyme twice. This is probably coincidental, since the ottava rima section does repeat two of these rhymes.9 On the other hand, the striking movement from "disintegration" to "reintegration" in the alliteration pattern is obviously premeditated. The translation reproduces both these features.

In the translation, the time of the action has been moved forward slightly (from late afternoon to just before sundown). Furthermore, in the first 33 lines of the translation, a hint in the imagery of the original (natural features in the landscape = heroic warriors) has been considerably expanded; this serves to provide a thematic link between the descriptive and narrative halves of the terza rima section.

There are four prior English translations of this poem: (1) by Mrs. Disney Leith (Three Visits to Iceland [London: J. Masters & Co., 1897], pp. 170-3); (2) by Rúnolfur Fjeldsted (IL51, 53, 55, 57); (3) by Skúli Johnson (Heimskringla [Winnipeg], LVI, 17 [21 January 1942], 2); and (4) by Hallberg Hallmundsson (Atlantica and Iceland Review, VI [1968], 1, 50-1).

Bibliography: Matthías Johannesen's chapter "Gunnarshólmi Jónasar" in his book Njála í íslenzkum kveðskap (Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag, 1958), pp. 72-84, contains an interesting account of the origin and evolution of the poem. Hannes Pétursson's chapter "Atriði viðvíkjandi Gunnarshólma" ("Some Points about 'Gunnar's Holm'"), in his book Kvæðafylgsni (Kf), also makes a number of interesting observations. For an analysis of the meter and formal structure of the poem, see Bbk50, 53-5, 69-71.

Notes

1 Frosti and Fjalar are dwarves whose names are mentioned in "The Sybil's Prophecy" ("Völuspá") in the Poetic Edda.

2 For details see Hreinn Haraldsson, "The Markarfljót Sandur Area, Southern Iceland: Sedimentological, Petrographical and Stratigraphical Studies," Striae 15 (Uppsala: Societas Upsaliensis pro Geologia Quaternaria, 1981), 3-58.

3 It is important — perhaps very important — to take into account at this point the following information provided by Vilhjálmur Þ. Gíslason:

Sigurður Breiðfjörð composed a set of rímur about Gunnar from Hlíðarendi that was published the year before Jónas wrote "Gunnar's Holm." It is probable that Jónas was familiar with, or had at least glanced through, some of these rímur. [Sigurður] devotes most of the eighteenth ríma to the incident of Gunnar's turning back. The ríma is in fact completely parallel to "Gunnar's Holm." The two poems show the response of two different generations of poets to the same subject matter, as well as their different poetic techniques and sensibilities. (JHF132)

They may also show Jónas's desire to compete with Sigurður on his own ground, a desire that manifests itself again in Jónas's "To Mr. Paul Gaimard," written only a year and a half after "Gunnar's Holm" and based (at least to some extent) on Sigurður's "Fjöllin á Fróni." There was no love lost between these two poets, as is shown by Sigurður's violent reaction to Fjölnir and Jónas's equally violent reaction to Sigurður's rímur.

4 Norðurljósið, 6. ár, 22. blað (30. nóvember 1891), 86. In another version of this anecdote, probably originating with Páll Melsteð, Bjarni and Sveinbjörn Egilsson ran into each other in Reykjavík one day not long after "Gunnar's Holm" had been published in Fjölnir. "My friend," said Bjarni, "I think the two of us can leave off writing poetry now. You've seen Jónas's latest piece?" (2BTL328-9)

5 But the first of these arguments is weak (the fact that Hallgrímur is sometimes wrong does not mean he is always wrong), the second weaker, and the third weakest of all: the testimony of both Páll Melsteð and Jónas himself makes it clear that he composed the first versions of two of his most outstanding poems ("To Mr. Paul Gaimard" and "Bjarni Thorarensen") in the space of a few hours, one of them while riding on horseback. And the first version of "Mount Broadshield," a poem even longer than "Gunnar's Holm," may well have been composed in a single day — once again during a journey on horseback. Steingrímur J. Þorsteinsson, who had thought about this question more deliberately than anyone else (see 2NH111-26), was convinced that for the most part Jónas composed his poems "in a single burst [of creative activity] over a short period of time" (ibid. 112). Revision, of course, was another matter.

6 Terza rima is a progressive rhyme scheme consisting of interlocking tercets (aba bcb cdc etc.), a sort of perpetuum mobile that forever resists resolution and closure. Poets' usual method of bringing about closure is to compose a single line that ends with the fresh rhyme introduced in the final tercet of the poem (i.e., the sequence of tercets concludes xyx yzy z). This is the invariable procedure of Chamisso (of whom more in a moment). Jónas, however, uses the rhyme in question as the pivot for his transition from terza to ottava rima. He may have felt that the usual way of ending poems in terza rima was abrupt and asymmetrical and therefore decided to anchor his own poem in two massive blocks of ottava rima. When the poem is read out loud, the effect of the long sequence of tercets followed by two stanzas of ottava rima is like — to use the ever-perilous musical analogy — a prolonged pedal-point whose tension is finally resolved by a series of solid foursquare chords.

7 Jónas's familiarity with Chamisso's poetry is shown by the fact that in January/February 1844 he translated the latter's "Küssen will ich, ich will küssen".

Chamisso specialized in terza rima and was regarded in his day as the great master of the form: he used it in over forty poems varying in length from fewer than twenty to more than three hundred lines. Several of these poems ("Die Ruine" and "Die Verbannten [I]") are like "Gunnar's Holm" in containing a narrative based on historical events and prefaced by (or interwoven with) elaborate descriptions of natural scenery. Chamisso's epic themes and his way of handling them may very well have suggested to Jónas how subject matter from Iceland's heroic past could be treated in a manner much more aesthetically appealing than that of the traditional Icelandic rímur.

Jónas was no doubt attracted to Chamisso in part because the latter — like Jónas himself — combined the roles of poet and natural scientist: Chamisso was a distinguished botanist who served in 1815-8 as official natural scientist on a Russian polar expedition making a three-year voyage round the world. He published a fascinating account of this voyage in 1836 in his collected works, and in 1837 produced a mongraph on the language of Hawaii. The scientific designations of a number of plants — including the state flower of California — still preserve Chamisso's name; so does an island in remote northwest Alaska.

If Jónas was indeed extensively familiar with Chamisso's poetry, which seems likely, he will probably have admired — perhaps even been influenced by — his fellow scientist's strong preference for objective representations of empirical reality: a preference shared by both poets, and one that saves both of them from some of the wilder excesses of Romanticism.

Chamisso is best known today for his "Peter Schlemihl's wundersame Geschichte" (1813), the famous tale of a man who sold his shadow to the devil. Jónas probably knew this work. And he will have enjoyed (if he knew it) Chamisso's German translation of the eddic "Þrymskviða" ("Lay of Þrymur")(1821), which imitates the metrical and alliterative structure of the original with remarkable success.

8 There seem to be several other verbal echoes of Chamisso's poem in Jónas's: blutigrot (Chamisso) / dreyrrauður (Jónas); Das tiefe Blau der Himmelswölbung oben (Chamisso) / í himinblámans fagurtæru lind (Jónas). Chamisso's poem, written and first published (in a periodical) in 1829, was subsequently included in the first collected edition of his poems (1831) and in his works (1836). The relationship between Jónas's poem and Chamisso's was first pointed out by Vilhjálmur Þ. Gíslason (JHF129).

9 Non-reoccurrence of a rhyme-set is not generally characteristic of Chamisso's poems in terza rima (though it does, in fact, happen in "Deutsche Barden").