|

|

|

Henry E. Legler, known so well in recent years as the popular and scholarly librarian of Chicago's great public library, was born in Palermo, Italy, June 22, 1861. He died in Chicago in September, 1917. He was educated in the schools of Switzerland and the United States. He married Nettie M. Clark, of Beloit, Wisconsin, in 1890. He was a member of the Assembly in 1889, secretary of the Milwaukee school board, 1890 to 1904, and secretary of the Wisconsin Library Commission, 1904 to 1909. In the latter year he wrote in a competitive examination set by the trustees of the Chicago public library and out of several applicants was unanimously chosen as being eminently the best fitted for the position of public librarian. The wisdom of that choice has never been questioned. Mr. Legler had in his makeup the rare combination of an ability to meet and mix with men on their own footing, together with the very highest and finest and soundest type of scholarship. This combination lends great charm to his many writings, as the brief selection here given amply testifies. He is the author of several books and pamphlets and was the contributor to many learned magazines. It would be hard to name any person in his field whose death would have been more keenly and genuinely felt. |

||

LEADING EVENTS OF WISCONSIN HISTORY

By HENRY E. LEGLER.

The Sentinel Company, Milwaukee, Wis., 1898.

LIFE IN THE DIGGINGSChapter VI, pages 165-168. |

|

|

|

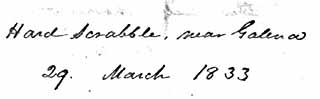

With the keen scent of birds of prey, gamblers and other adventurers flocked to the lead diggings of southwestern Wisconsin during the great mining excitement that occurred in the early '20's. As was the case later in California, gambling dens and grog shops were constructed in the midst of the cabins of the miners, and the fruit of the prospector's thrift often went into the coffers of the card shark. During the years when the lead mines were being developed, the aggregation of cabins that dotted the region were the typical frontier camps of a mineral country, with their swagger and utter disregard of any law but their own--prototypes of the later gulch towns of the far West. Their names were characteristic, too, and some of them yet retain a place on the map of Wisconsin. Among them were Hardscrabble Diggings, Buncome, Snake Hollow, Shake-the-Rag-Under-the-Hill, Rattle Snake Diggings, Big Patch, and other places with more euphonious, if less descriptive, names. |

Map of the Lead Mining District |

|

|

||

Nicholas Boilvin |

It was about 1822 that the so-called discovery of the lead diggings in southwestern Wisconsin occurred. For nearly two centuries the existence of the ore in that region had been known to white men, but the Indians were unwilling to let them penetrate to the mines. This was especially the case when the pushing Americans began to travel from the southern states to the upper Mississippi in quest of fortune. Before this, Frenchmen had been given permission to work the mines to some extent, for the Indian was ever wont to fraternize with the representatives of this volatile race, but Americans were rigidly excluded. The introduction of firearms among the Indians had taught them the value of the lead as an article of barter. It was stated in a letter written to the secretary of war in 1810 by Nicholas Boilvin, agent at Prairie du Chien, that the quantity of lead exchanged by Indians for goods during the season was about 400,000 pounds. |

Mrs. Nicholas Boilvin |

|

Doubtless none but Frenchmen had been at the mines previous to the war of 1812, but in 1816 a St. Louis trader named John Shaw succeeded in penetrating to the mines of the Fever river district by passing himself as a Frenchman. He was one of the traders who made periodical trips to Prairie du Chien, propelling the boats by means of poles and sails. It required from two weeks to a month to make the trip up the river, while the return journey occupied from a week to ten days. The boats carried miscellaneous supplies to Prairie du Chien, and their return cargo consisted principally of lead. Shaw saw about twenty smelting places, the mineral being smelted in the crudest way imaginable. This was Shaw's description of the process: "A hole or cavity was dug in the face of a piece of sloping ground, about two feet in depth and as much in width at the top; this hole was made in the shape of a mill-hopper, which was about eight or nine inches square; other narrow stones were laid across grate-wise; a channel or eye was dug from the sloping side of the ground inwards to the bottom of the hopper. This channel was about a foot in width and in height, and was filled with dry wood and brush. The hopper being filled with the mineral, and the wood ignited, the molten lead fell through the stones at the bottom of the hopper; and this was discharged through the eye, over the earth, in bowl-shaped masses calIed plats, each of which weighed about seventy pounds." |

||

Galena lead mine |

Glowing notices of the richness of the lead mines of the upper Mississippi appeared in St. Louis newspapers in 1822, and started a migration thitherward. In order to overawe the Indians, who would not let white men enter the district, the government dispatched detachments of troops from Prairie du Chien and the Rock Island forts. Finding that resistance would be futile, the Indians quietly submitted to the invasion of their mineral territory. Thus began, a few miles south of the present border of the state, what at one time was the leading industry of Wisconsin, as the fur trade had been up to that period. The newcomers were mainly from the southern states and territories, and thus the first seeds of American origin in Wisconsin were the planting of men from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri. They came by boat and in caravans on horseback. Soon the prospector's shovel was upturning the sod on the hillsides of southwestern Wisconsin, the Indian occupants in sullen resentment biding their time for mischief. Galena became the center of the mining region. |

|

|

Some of the adventurers who came in the expectation of acquiring sudden wealth were doomed to disappointment. There were some who sought to avoid the rigors of the northern winter by coming in the spring and returning to their genial southern climate when snow began to fly. These tenderfeet were denominated "suckers" by the hardier miners, an appellation that was later transferred to the state of Illinois. Their superficial workings were called "sucker holes." |

||

|

Despite muttered threats from the Indians, and other disheartening circumstances, population rapidly increased. Red Bird's disturbance caused a temporary exodus, but the frightened miners soon returned. How busily pick and shovel were plied may be gathered from the reports of lead manufactured. It was soon seen that negro labor could be well utilized, and some of the southerners brought slaves to do the work. The population rapidly increased. In 1825 it was estimated that there were two hundred persons; three years later fully ten thousand, one-twentieth being women and about one hundred free blacks. The lead product had increased in the same period from 439,473 pounds to 12,957,100 pounds. |

|

|

Moses Meeker |

Most of the miners followed the Indian plan of smelting in a log furnace. It was a crude device, and there was much wastage. They likewise imitated the Indian mode of blasting--heating the rock and then splitting it by throwing water on it. "I saw one place where they (the Indians) dug forty-five feet deep," says the account of Dr. Moses Meeker, a pioneer of the period. "Their manner of doing it was by drawing the mineral dirt and rock in what they called a mocock, a kind of basket made of birch bark, or dry hide of buckskin, to which they attached a rope made of rawhide. Their tools were a hoe made for the Indian trade, an axe, and a crowbar made of an old gun barrel flattened at the breech, which they used for removing the rock. Their mode of blasting was rather tedious, to be sure; they got dry wood and kindled a fire along the rock as far as they wished to break it. After getting the rock hot they poured cold water upon it, which so cracked it that they could pry it up. At the old Buck Lead they removed many hundred tons of rock in that manner, and had raised many thousand pounds of mineral or lead ore." |

Henry Dodge |

William S. Hamilton |

During this period there came to Wisconsin some of the men who became most notable in its territorial history. Among them were Henry Dodge, afterwards governor, who brought with him from Missouri a number of negro slaves; Ebenezer Brigham, pioneer of Blue Mounds; Henry Gratiot and Col. William S. Hamilton. The latter was a son of Alexander Hamilton, who was killed by Aaron Burr, in a duel. Some of the miners realized what in those days were considered great fortunes. One man sank a shaft near Hazel Green on the site of an old Indian digging. "At four and a half feet he found block mineral extending over all the bottom of his hole," in the language of Dr. Meeker's narrative. "He went to work and cut out steps on the side of the hole, to be ready for the next day's operation. Accordingly, the next day he commenced operations. The result of his day's work was seventeen thousand pounds of mineral upon the bank at night." After raising about a hundred thousand pounds, the diggings was abandoned. Another prospector took possession and secured more than a hundred and fifty thousand pounds. |

Henry Gratiot |

Hazel Green mine pit |

Lead Mine |

|

Mineral Point |

Most of the lead that was smelted went to Galena, to be transported thence to St. Louis and New Orleans. Long caravans of ore wagons, some of them drawn by as many as eight yoke of oxen, wore deep ruts into the primitive road that went by way of Mineral Point and Belmont to this metropolis of the mines. About $80 a ton was obtained for the ore. About 1830, tariff agitation seems to have caused a great drop in prices. At this period the federal government exacted from the miners what was known as a lead rent. The miners addressed a memorial to the secretary of war, whose department had control of the collection of the mineral rents, complaining of excessive taxation. The claim was made by them in their memorial "that they have paid a greater amount of taxes than any equal number of citizens since the settlement of America!" The smelters were required to pay ten per cent of all lead manufactured and had to haul the rent lead a distance of fifty to sixty miles to the United States depot. It was not until 1846 that Congress abandoned the leasing system. |

Settled Area in 1830 |

|

Doubtless the typical mining camp in Wisconsin when the lead excitement was in its heyday was Mineral Point. Its straggling lines of huts were ranged along a deep gorge, and at all hours the sound of revelry could be heard emanating from the saloons and gambling houses. Dancing and singing, with the accompaniment of rude music, and drinking and gambling furnished the entertainment for the wilder spirits. The town bore the appellation of the Little Shake-Rag, or Shake-Rag-Under-the-Hill. The origin of the peculiar name is explained by an early-day traveler in this wise: |

pioneer windlass |

Cassville leadmines |

"Females," says this account of sixty years ago, "in consequence of the dangers and privations of the primitive times, were as rare in the diggings as snakes upon the Emerald Isle. Consequently the bachelor miner from necessity performed the domestic duties of cook and washerwoman, and the preparation of meals was indicated by appending a rag to an upright pole, which, fluttering in the breeze, telegraphically conveyed the glad tidings to his hungered brethren upon the hill. Hence this circumstance at a very early date gave this provincial sobriquet of Shake-Rag, or Shake-Rag-Under-the-Hill." |

Cassville leadmines |