|

|

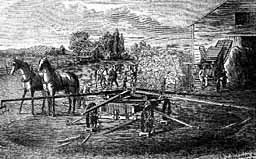

THE OLD FASHIONED THRESHING IN GREEN'S *COULEE, WISCONSIN

From "BOY LIFE ON THE PRAIRIE." Published by permission of

Harper and Bros.

Life on a Wisconsin farm, even for the older lads, had its compensations. There were times when the daily routine of lonely and monotonous life gave place to an agreeable bustle for a few days, and human intercourse lightened toil. In the midst of the dull, slow progress of the fall's ploughing, the gathering of the threshing crew was a most dramatic event. There had been great changes in the methods of threshing since Mr. Stewart had begun to farm, but it had not yet reached the point where steam displaced the horse-power; and the grain, after being stacked round the barn ready to be threshed, was allowed to remain until late in the fall before calling in a machine. Of course, some farmers got at it earlier, for all could not thresh at the same time, and a good part of the fall's labor consisted in "changing works" with the neighbors, thus laying up a stock of unpaid labor ready for the home job. Day after day, therefore, Mr. Stewart and the hired man shouldered their forks in the crisp and early dawn and went to help their neighbors, while the boys ploughed the stubble-land. |

Grand Dad's Bluff |

|

All through the months of October and November, the ceaseless ringing hum and the bow-ouw, ouw-woo booee-oom of the great balance wheel of the threshing-machine, and the deep bass hum of the whirling cylinder, as its motion rose and fell, could be heard on every side like the singing of some sullen and gigantic autumnal insect. Lincoln had looked forward to the coming of the threshers with the greatest eagerness, and during the whole of the day appointed, Owen and he hung on the gate and gazed down the road to see if the machine were coming. It did not come during the afternoon-still they could not give it up, and at the falling of dusk still hoped to hear the rattle of its machinery. It was not uncommon for the men who attended to these machines to work all day at one place and move to another setting at night. In that way, they might not arrive until 9 o'clock at night, or they might come at 4 o'clock in the morning, and the children were about starting to "climb the wooden hill" when they heard the peculiar rattle of the cylinder and the voices of the McTurgs, singing. |

threshing scene |

|

"There they are," said Mr. Stewart, getting the old square lantern and lighting the candle within. The air was sharp, and the boys, having taken off their boots, could only stand at the window and watch their father as he went out to show the men where to set the "power," the dim light throwing fantastic shadows here and there, lighting up a face now and then, and bringing out the thresher, which seemed a silent monster to the children, who flattened their noses against the window-panes to be sure that nothing should escape them. The men's voices sounded cheerfully in the still night, and the roused turkeys in the oaks peered about on their perches, black silhouettes against the sky. The children would gladly have stayed up to greet the threshers, who were captains of industry in their eyes, but they were ordered off to bed by Mrs. Stewart, who said, "You must go to sleep in order to be up early in the morning." As they lay there in their beds under the sloping rafter roof, they heard the *hand riding furiously away to tell some of the neighbors that the threshers had come. They could hear the cackle of the hens as Mr. Stewart assaulted them and wrung their innocent necks. The crash of the "sweeps" being unloaded sounded loud and clear in the night, and so watching the dance of the lights and shadows cast by the lantern on the plastered wall, they fell asleep. They were awakened next morning by the ringing beat of the iron sledge as the men drove stakes to hold the "power" to the ground. The rattle of chains, the clang of iron bars, intermixed with laughter and snatches of song, came sharply through the frosty air. The smell of sausages being fried in the kitchen, the rapid tread of their busy mother as she hurried the breakfast forward, warned the boys that it was time to get up, although it was not yet dawn in the east, and they had a sense of being awakened to a strange, new world. When they got down to breakfast, the men had finished their coffee and were out in the stock-yard completing preparations. |

Mounted Carey Power |

|

This morning experience was superb. Though shivery and cold in the faint frosty light of the day, the children enjoyed every moment of it. The frost lay white on every surface, the frozen ground rang like iron under the steel-shod feet of the horses, the breath of the men rose up in little white puffs while they sparred playfully or rolled each other on the ground in jovial clinches of legs and arms. The young men were anxiously waiting the first sound which should rouse the countryside and proclaim that theirs was the first machine to be at work. The older men stood in groups, talking politics or speculating on the price of wheat, pausing occasionally to slap their hands about their breasts. Finally, just as the east began to bloom and long streamers of red began to unroll along the vast gray dome of sky, Joe Gilman-"Shouting Joe," as he was called-mounted one of the stacks, and throwing down the cap-sheaf, lifted his voice in a "Chippewa warwhoop." On a still morning like this his voice could be heard three miles. Long drawn and musical, it sped away over the fields, announcing to all the world that the McTurgs were ready for the race. Answers came back faintly from the frosty fields, where the dim figures of laggard hands could be seen hurrying over the ploughland; then David called "All right," and the machine began to hum. |

Buffalo Pitts Thresher |

|

In those days the machine was a J. I. Case or a "Buffalo Pits" separator, and was moved by five pairs of horses attached to a power staked to the ground, round which they travelled to the left, pulling at the ends of long levers or sweeps. The power was planted some rods away from the machine, to which the force was carried by means of "tumbling rods," with "knuckle joints." The driver stood upon a platform above the huge, savage, cog-wheels round which the horses moved, and he was a great figure in the eyes of the boys. |

|

|

Driving looked like an easy job, but it was not. It was very tiresome to stand on that small platform all through the long day of the early fall, and on cold November mornings when the cutting wind roared over the plain, sweeping the dust and leaves along the road. It was far pleasanter to sit on the south side of the stack, as Tommy did, and watch the horses go round. It was necessary also for the driver to be a man of good judgment, for the power must be kept just to the right speed, and he should be able to gauge the motion of the cylinder by the pitch of its deep bass hum. There were always three men who went with the machine and were properly "the threshers." One acted as driver; the others were respectively "feeder" and "tender"; one of them fed the grain into the rolling cylinder, while the other, oil-can in hand, "tended" the separator. The feeder's position was the high place to which all boys aspired, and they used to stand in silent admiration watching the easy, powerful swing of David McTurg as he caught the bundles in the crook of his arm, and spread them out into a broad, smooth band upon which the cylinder caught and tore like some insatiate monster, and David was the ideal man in Lincoln's eyes, and to be able to feed a threshing machine, the highest honor in the world. The boy who was chosen to cut bands went to his post like a soldier to dangerous picket duty. |

Case Thresher |

|

Sometimes David would take one of the small boys upon his stand, where he could see the cylinder whiz while flying wheat stung his face. Sometimes the driver would invite Tommy on the power to watch the horses go round, and when he became dizzy often took the youngster in his arms and running out along the moving sweep, threw him with a shout into David's arms. The boys who were just old enough to hold sacks for the measurer, did not enjoy threshing so well, but to Lincoln and his mates it was the keenest joy. They wished it would never end. |

*In his latest book, "A Son of the Middle Border," 1917, Mr. Garland adopts this spelling in place of "Coolly," which he formerly used.

*The hired man.